|

.

| This page will

contain articles written to share some of my ideas about playing

music. I welcome your feedback

about these articles, whether it is to say they have been of

help, dispute my approach, or correct some grievous error I have

made.

.

|

Strategies For Improvising Part I "The Right Note at the Right Time" Strategies For Improvising Part I "The Right Note at the Right Time"

Let's assume you know a couple of scales, and you know what it means to play in a key. You are ready to start playing solos on a favorite song and wonder how to get started. You have learned the original artist's solo note for note and now you want to try improvising your own solo. Improvising is essentially the skill of composing music as is it being played. The best improvisers do this so smoothly and flawlessly that is almost impossible to tell when they are playing music that has been prepared vs when they are making it up as they go.

The task of learning to improvise seems daunting when we first attempt it. Even the best improvisers have strategies to help guide them, ideas that provide a sense of structure. This structure acts as a guide and allows them to create consistently good music almost instantly.

Often the first time a student is exposed to the idea of improvising is shortly after learning a simple scale such as the minor pentatonic scale, sometimes called "the blues scale". Pentatonic scales have only five notes, chosen to be as inoffensive sounding as possible. They provide a relativity high success rate even if you just randomly play the notes against a set of chord changes. To my ears, a lot of players don't ever go much farther than that random approach, hunting and pecking through a few notes until they find one that sounds good to them. One thing that sets apart great improvisers is that they always play the "right" notes. Their note choices aren't random at all, they choose specific notes at specific times to compliment the chords that are being played.

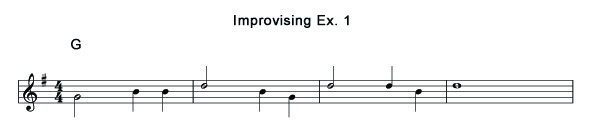

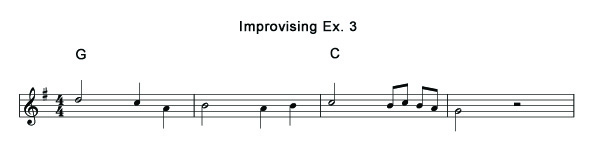

What makes a note compliment a chord? In other words, why does one note sound good when a chord is being played and another doesn't sound as good? I admit, at some point this boils down to taste, music is art after all. If it sounds good it is good. In the beginning, however, we need a strategy to simplify our note choices and give us a 100% chance of choosing a note that sounds good. For our purposes I will define the "right" note as simply a note that is contained within the chord being played at that time. For example, let's look at a simple song in the key of G. The rhythm guitarist is strumming a G chord so we will choose to play any of the three notes that are found in the G chord, the G, B and D notes. I refer to these notes as the "chord tones". There is no way that at any time the G chord is being played you can ever sound "wrong" if you play one of it's chord tones. It doesn't have to be the root note, the G. The B or the D will work just as well.

Listen to an example of improvising using only the chord tones of the G chord

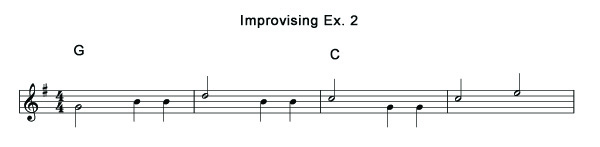

When the rhythm guitarist changes to a new chord we must also change the notes that we play to compliment this new chord. If the chord is now a C our new chord tones are the notes C, E, and G. These are the notes that make up the C chord. We will now choose to play one of those three notes over the C chord, and again, no matter which one we choose it will sound good.

Listen to an example of improvising using only chord tones over a chord progression that includes two measures of G followed by two measures of

C

Are chord tones the only notes we are allowed to play? Absolutely not. Ideally we will use many or all of the notes of a scale. If the chord is a G chord we would refer to the notes G, B and D as the chord tones. The other notes of the G scale can be referred to as "passing tones". We can play them, but we want to move through them, "passing" them on the way to a chord tone. We can play passing tones, but we de-emphasize them. The chord tones are the most important notes, the ones that always sound good, so we want to emphasize them. We can do this by playing them with a longer duration or playing them on a strong beat such as the

first beat of a measure. What makes a note feel "right" is not only that it is a chord tone but also that you play it at the right time to emphasize it. The simplest strategy is to make sure that you play a chord tone on the downbeat of the first measure of a chord. This first beat of each measure is the where we put the most emphasis and it is the note the listener will pay the most attention to. If that note is a chord tone then we are sure to sound like we know what we are doing. We can then play other chord tones or passing tones on the other beats of the measure and it will sound fine. Those notes become stepping stones leading us to the strong beat.

Listen to an example of improvising using a chord tone on the first beat of each measure, and passing tones played on the weaker

beats

In the above example each note that falls on the downbeat is a chord tone, and is further emphasized by being held for two beats. This combination of strategies makes those notes the most important notes, and the passing tones are barely noticed.

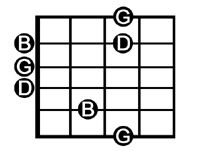

The most daunting aspect of this strategy is learning what the chord tones of each chord are. There are several ways to accomplish this. You can memorize them for chords you commonly use. You can use a theory based approach and find the root, third and fifth of the chord. One method I use on stringed instruments is to visualize chords on the fretboard. Since a chord tone is nothing more than a note in the chord any note that you would hold down when playing a chord is one of those notes. Talk with your instructor about more ways to implement these strategies in your playing.

This chart gives chord tones for the most common chords in the key of G.

|

| Chord |

1 |

3 |

5 |

| G |

G |

B |

D |

| C |

C |

E |

G |

| D |

D |

F# |

A |

This note chart shows chord tones for the G chord in the open position of a guitar. Note that the chart looks almost exactly like a common G chord.

|

"I

didn't Have Time To Practice This Week" "I

didn't Have Time To Practice This Week"

September 13, 2012

Often students come to a lesson frustrated and tell me that they haven't had any time to practice this week. Sure, life gets in the way, and sometimes we just don't have time to pick up an instrument. However this doesn't mean that we can't continue our study of music. In fact, some of the most educational experiences we can have as we learn about music happen without an instrument in our hands. I will go so far as to say that these lessons are at least as important as the practice time we have with our instrument.

Critical Listening

How much time do you spend driving in a car? Or exercising? (If you are like me, the answer is "not enough".) Or any number of other activities where your mind is relatively free to focus on listening to music. I know a lot of people who claim they listen to music all the time. They have the radio or TV on all day, they play music while they work or while they do chores at home. But rarely do people actually do what I call "critical listening". Most people let the sound of music wash over them, enjoying the beat, singing along to familiar songs, but rarely paying careful attention to the music itself.

The next time you drive to work pop in a great CD and listen to a favourite song. Learn something you never knew about it. Listen to each instrument separately and try to think about what each one plays, and what role it serves in the band. Does one instrument drive the rhythm or is it a combination of two or more instruments that create the pulse? Hear how two instruments interact with one another, how they compliment one another or how they stay out of each other's way. Sing a harmony when there isn't one in the recording. When the singer sings what else is going on musically? Is there a backup melody instrument playing? Does it play over top of the vocal or does it weave in and around the melody? Does one part of a song really get you excited? Why is that? Maybe the dynamics change, or the tempo, perhaps a singer or an instrument hits a particularly high note at just the right time. What style of music are you listening to, and does it have a signature element that defines it compared to other styles of music? There is so much to learn from the great players and from bands who have created complex arrangements for their songs. The list of things to discover is endless, but if you uncover only one small aspect of the music that you love and analyze how it works then you have a new tool that you can apply to your own playing.

Rhythm

One of the most common problems my beginner students have is developing a strong sense of rhythm. Some people can hear a pattern and repeat it easily while others struggle and must count it out. We can develop our sense of rhythm without the need for an instrument. As long as we can clap, tap, snap, or hum we can practice rhythm. In fact, I find that eliminating the instrument removes some distractions such as trying to change notes, focusing on hitting specific strings, and other mechanical issues that a learner may be struggling with. The next time you find yourself with your hands free for a few minutes try some rhythm exercises. You can tap out a syncopated rhythm on the steering wheel of your car, or tap your foot under your desk. One of my favourite rhythm exercises is to subdivide the beat by tapping out first quarter notes, then switching to eight notes, then sixteenths, etc. I add triplets as well, and once I can switch back and forth in a controlled manner I mix them up at random. I usually keep a pick in my pocket and will occasionally practice this exercise with my pick in my hand by playing my pants leg. This might earn you funny looks on the subway but the family will appreciate how quiet the exercise is, and you can do it sitting on the couch watching a TV show you really aren't interested in.

Visualization

I am a visual learner. When I think of music I almost always create some mental picture. For example when I think of the intervals between notes I often see in my mind their positions on the fretboard, and those patterns inform me. I realize that not everyone thinks this way, but for those of us that do visualization can be a powerful tool. It is not unusual for me to lay in bed at night thinking about a song I am learning or new scale pattern I am working on. I go through it slowly, imaging the fretboard and "seeing" where the notes are located. Sometime my left hand will join in the process and my fingers will "play" the notes as I progress mentally through my song or scale. Again, this technique may not work well for everyone, but if it works for you I guarantee it is more productive than counting sheep!

Ear Training

I am an alpine skier and one of my favourite ways spend the five minutes or so on the ski lift is doing ear training exercises. I may sing intervals, such as singing a random note and thinking of it as the first note of scale, then singing other notes of the scale at random. Or I may sing a half step and then a whole step above and below the original note. This trains my voice and also keeps my ears attuned to the sounds of intervals. Another technique I use to is to play music (I have headphones built into my ski helmet) and listen for the intervals of the melody, or listening for the chord changes. Sometimes I can learn an entire song this way, not by knowing the names of the chords but by their musical relationships such as the IV chord or the V chord. Then when I have an instrument in my hand I just pick out the key based on sound and then I have a huge head start at learning to play the song, since I already know the chord structure and maybe have some idea of how the melody goes. Admittedly these are techniques that someone just starting to learn to play an instrument is unlikely to have command of, but I feel that in all the formal musical training I have received my ear training classes have been some of the most useful. Ask your instructor how you can learn more about these wonderful techniques.

I hope this gives you some ideas for how you can continue your musical education or just stay sharp and focused even when formal practice time is limited. Hopefully the morning commute will never be the same, and being caught in traffic or having a sleepless night may now be a blessing in disguise.

.

|

Alternating

Rhythm Exercises Alternating

Rhythm Exercises

September 14, 2012

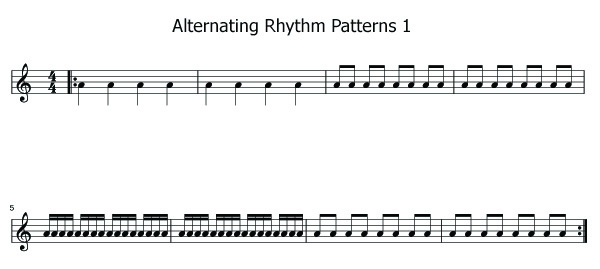

In the above article "I

didn't Have Time To Practice This Week" I mentioned a

rhythm exercise that I regulary practice to keep my muscles and

brain capable of smoothly shifting between rhythmic patterns,

such as a series of eighth notes and a series of eight note

triplets. When I practice these on an instrument such as

the mandolin I play an open string and don't use the left hand

at all. I follow the standard practice of picking down on

the beat and up in between the beat, so a string of quarter

notes will all be picked down and a series of eighth notes will

be picked down-up, down-up, etc.

This exercise is a

good warm up, as you have two full measures of each pattern

before moving on to a new one. If you need more time increase

the repetitions to four measures of each pattern. You may

substitute any rhythmic pattern that you wish to practice, such

as eighth note triplets.

Hear

this exercise played

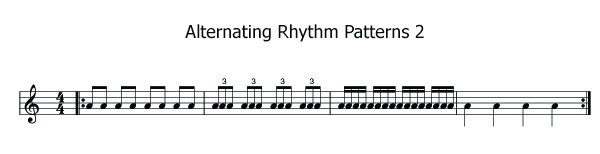

Next, we increase the difficulty

by shortening the repetitions to only one measure of each

pattern. I have added triplets to this exercise.

Hear

this exercise played

As you become more and more

proficient switching between rhythm patterns shorten the

repetitions, and mix up patterns within measures. If you

are learning a song and find that a specific measure or measures

have particulaly tricky rhythms make that pattern an

exercise. Keep in mind you can do these exercises

anywhere, anytime, even when you dont have an instrument

handy. You can practice with just a pick or tap a table

top.

.

|

|

"If

You're Thinkin' You're Stinkin' " "If

You're Thinkin' You're Stinkin' "

August 1, 2012

Music legend Steve

Miller was a frequent customer at a music store where I taught for

some years and I had the opportunity to talk with him on occasion about

his approach to playing music. One phrase that he used has stuck

with me and that's where the title of this article comes from. "If

you're thinkin' you're stinkin' ". Steve never particularly

elaborated on that statement, but it has taken on a special meaning to

me. Simply put, I think it means "be

prepared".

Music happens in a constant stream.

When we perform there is no time to think about where we are at the

moment. By the time you think about that the moment has

passed. What I believe Steve was telling us is that in order to be

ready to perform a song we need to have already spent many hours doing all

the "thinkin' ". When performing we don't have the time to

wonder what the next chord is, let alone the next note. We

need to have prepared ahead of time and memorized each aspect of the song

such as chord changes, the melody, the words, the structure, etc.

Create a solo or practice improvising over the chord changes. Know

whether the bridge follows the solo or whether it goes back to a

chorus. Don't read the words from a cheat sheet (something I have

been horribly guilty of). Not being prepared leads to hesitation,

and when performing music there is no time to waste.

Are you ready to perform a song?

Practice it all the way through by memory without stopping. Does it

flow or are you trying to remember what comes next? A good rule of

thumb for me is that if I have the mental capacity to focus on details

such as timing, tone, expressiveness, planning for an improvised solo

before I begin to play it, then I know that the song has been

internalized. Like an old computer I have limited memory, so if I am

having to think about the basics I don't have the capacity to focus on the

nuances.

.

.

|

|

Why Playing Music

is Like Time Travel Why Playing Music

is Like Time Travel

July 31, 2012

As an unabashed nerd,

some of these articles may have nonsensical titles such as this

one, but I hope that the information presented will be less

esoteric.

One of the ideas that

I often see presented about playing music is that it should

"flow", coming out smoothly and naturally. This is

certainly true. I also hear the phrase "in the

moment" by which I assume people mean that you are focused on

what you are doing, ignoring distractions, and letting yourself

connect to the music you are playing. These things are true,

but they relate to the "now". What I want to talk

about is how we relate to the future when we play. Although

that may sound a little fruity at first, almost everything that we

do when we play is about reaching forward towards some other

moment in time.

As a beginner we are

focused on the basics. Playing the right notes, fretting

them cleanly, connecting our right hand and left hand

motions. Even on that level the future becomes an important

part of how we play. Picking motions don't occur at one

instant of time, but rather we start moving the hand slightly

before the beat we want to play. We put a finger down on a

fret a split second before the pick hits the string. In

almost every way we anticipate the next note, or the next beat,

and we go into motion ahead of time in order to arrive at just the

right moment. By the time the first eighth note of a fiddle

tune has begun to ring out we had better be thinking about and

moving towards the second one. When it comes time to change

chords we have to make a whole series of motions quickly and

effeciently to be in place a split second before the pick strikes

those strings on the next beat. In this way we have to be

thinking about what happens next, and we cannot afford the time to

get caught up in the "now".

As we begin to learn

songs notes are grouped in combinations we refer to as

phrases. Musical phrases are much like a written or spoken

sentence or sentence fragment: a combination of notes, as opposed

to words, whose meaning becomes important in the way they are

grouped together. Phrases occur over the course of one more

measures. At this point the goal we have in mind is to

completete our phrase. The completion of that goal is now a

second or more into the future. As you play you may see this

goal in sight, and begin to hear your notes not as indiviuals but

as a stream of sounds that all lead to a single point, creating a

coherent musical thought. This is when our performance has

the opportunity to become more nuanced. We can now shape the

phrase to add feeling, playing it quietly, or loudly, perhaps

crescendoing to a final note. It is the completed phrase

that matters most, and individual notes may be given different

emphasis with that final goal in mind. Before we play the next

note we have imaged the completed phrase, and how each note can

best fit into the pattern.

The idea of thinking

into the future is probably best illustrated when it comes to

improvisation, one of my favourite aspects of playing music.

I will talk a lot more about improv techniques, but for now let me

limit my thinking to a single concept (that I will talk more about

in other articles) which I call "Playing the Right Note at

the Right Time". In it's most basic form I will say

this is playing a chord tone on the downbeat of the measure.

That means playing a note contained with the chord that is

currently played by an accompanist on the first beat of a new

measure. If the song is on a C chord the improviser can play a

C, E, or G note. That downbeat, the first beat of the

measure, is going to be the end of our phrase. Rather than

starting to play forward from that moment I suggest a more lyrical

approach, which is thinking towards that moment. Thinking towards

the future. In the measure or measures before this note

takes place I will start playing through my scale with the

intention of creating a musical phrase that ends on that chord

tone on the downbeat. This creates a coherent thought

that ends on a note that is in harmony with the music being

played. The way we do this is by looking ahead, knowing the

future of the music we will play, and making choices now to

reflect what is coming.

|

|

|

. |